What is Inversion?

Inversion is a powerful mental model that helps us think in reverse. Instead of asking, "How can I succeed?" you ask, "What would cause me to fail?" By identifying obstacles, mistakes, and risks beforehand, we can actively work to avoid them, leading to better decision-making.

In simple terms, inversion means thinking backwards to move forward. It is famously used in mathematics and philosophy, especially in problem-solving, where thinking of the opposite scenario often provides clarity.

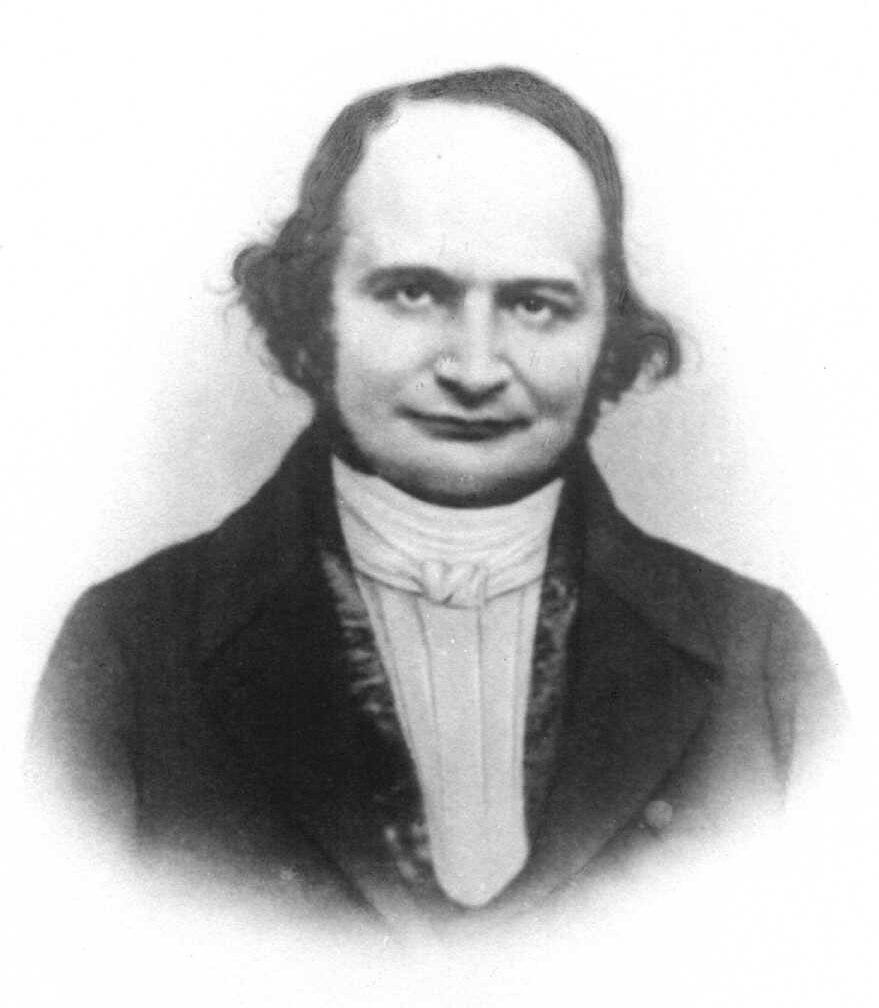

The mathematician Carl Gustav Jacob Jacobi, known for his work in number theory, famously said, "Invert, always invert." He believed that many difficult problems could be solved more easily by considering their inverse. This principle has been widely adopted in various fields, including finance, business, and strategic thinking.

Why Do We Need Inversion?

We often approach problems with a forward-thinking mindset, focusing only on what we should do. However, we ignore the pitfalls that could derail our efforts. Inversion helps us:

Avoid common mistakes.

Identify blind spots.

Improve decision-making.

Solve complex problems efficiently.

Successful thinkers like Charlie Munger (Warren Buffett’s business partner) and ancient Indian philosophers like Chanakya emphasized the importance of looking at problems from a reverse perspective.

Application of Inversion in Daily Life

Let’s undertake 02 case studies to understand Principle of Inversion effectively.

1. Business Case Study: Toyota’s Production System

In the 1950s, Toyota was a struggling automaker aiming to compete with American giants like Ford. They developed the Toyota Production System (TPS), a cornerstone of modern lean manufacturing. Inversion thinking played a key role in its design.

Traditional Goal: "How do we build cars efficiently and profitably?"

Focus: Increase output, reduce costs, improve quality.

Inversion Question: "What would cause our production to fail or waste resources?"

Answers:

Overproduction leads to unsold inventory.

Defects force costly rework or recalls.

Idle workers or machines waste time and money.

Supply delays halt assembly lines.

Actions Taken Using Inversion:

Overproduction: Toyota implemented the "Just-In-Time" (JIT) system, producing only what was needed based on demand, avoiding excess stock.

Defects: They introduced "Jidoka" (automation with a human touch), empowering workers to stop the line if a flaw was spotted, fixing issues immediately rather than letting them pile up.

Idle Time: The "Kaizen" philosophy encouraged continuous small improvements to eliminate inefficiencies, keeping workers and machines active.

Supply Risks: Close partnerships with suppliers ensured timely deliveries, with backup plans for disruptions.

By 1980, Toyota became a global leader, surpassing many Western competitors. JIT reduced inventory costs by millions annually (e.g., Ford held $1 billion in stock vs. Toyota’s lean approach). Defect rates dropped (Toyota’s cars had fewer recalls than Detroit’s Big Three), and productivity soared—Toyota workers assembled cars in half the time of U.S. counterparts by the 1990s. The TPS saved billions over decades and is now a gold standard in manufacturing.

Evidence of Success: Toyota’s market cap hit $200 billion by the 2000s, while competitors like GM faced bankruptcy in 2009. Inversion turned potential failures into a competitive edge.

2. Government Case Study: Singapore’s Water Management

In the 1960s, Singapore, a small island nation, relied heavily on imported water from Malaysia, facing vulnerability as its population grew. The government used inversion thinking to achieve water self-sufficiency.

Traditional Goal: "How do we ensure a stable water supply for our people?"

Focus: Build reservoirs, secure imports, encourage conservation.

Inversion Question: "What would cause us to run out of water?"

Answers:

Droughts dry up local reservoirs.

Malaysia cuts off our imported supply (political or economic leverage).

Pollution ruins existing water sources.

Population growth outpaces supply capacity.

Actions Taken Using Inversion:

Drought Risk: Singapore built the Marina Barrage and expanded reservoirs, while pioneering NEWater—recycled wastewater purified to drinking standards—reducing reliance on rainfall.

Import Dependence: They invested in desalination plants (e.g., Tuas Desalination Plant) to tap seawater, cutting import needs.

Pollution: Strict regulations and the cleanup of rivers like the Singapore River ensured local sources stayed viable.

Demand Growth: Public campaigns (e.g., “Water is precious”) and pricing policies curbed usage, while infrastructure scaled ahead of population booms.

By 2025, Singapore meets ~100% of its water needs domestically. NEWater supplies 40% of demand, desalination 30%, and reservoirs/imports cover the rest. Imports from Malaysia, once 80% of supply in 1965, are now a backup (projected to hit zero by 2061 when the water agreement expires). The nation avoided water crises during droughts (e.g., 2014), and per capita usage dropped from 165 liters/day in 2003 to 141 liters/day in 2020. The strategy saved billions in potential import costs and bolstered national security.

Checklist to Apply Inversion in Decision-Making

Define your goal clearly.

Ask: "What can go wrong?"

Identify common mistakes or failures in similar situations.

Find ways to eliminate or minimize these risks.

Implement strategies that prevent failure instead of just chasing success.

Review and adjust continuously.

By thinking in reverse, we often gain clearer insights than by thinking in a straight line. So, next time you’re stuck, don’t just ask, “What should I do?”—ask, “What should I not do?” That’s the power of Inversion!

Best Wishes !