What is Falsifiability?

Falsifiability is a principle that states that for an idea, theory, or belief to be considered scientific or rational, it must be possible to prove it wrong. If there is no way to test whether a claim is false, then it remains in the realm of speculation or faith rather than logic and evidence.

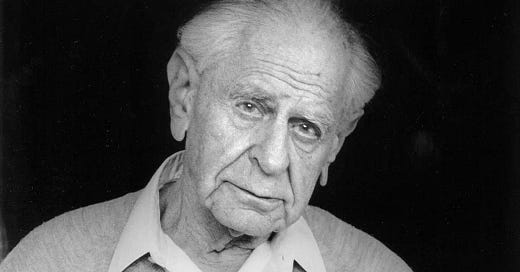

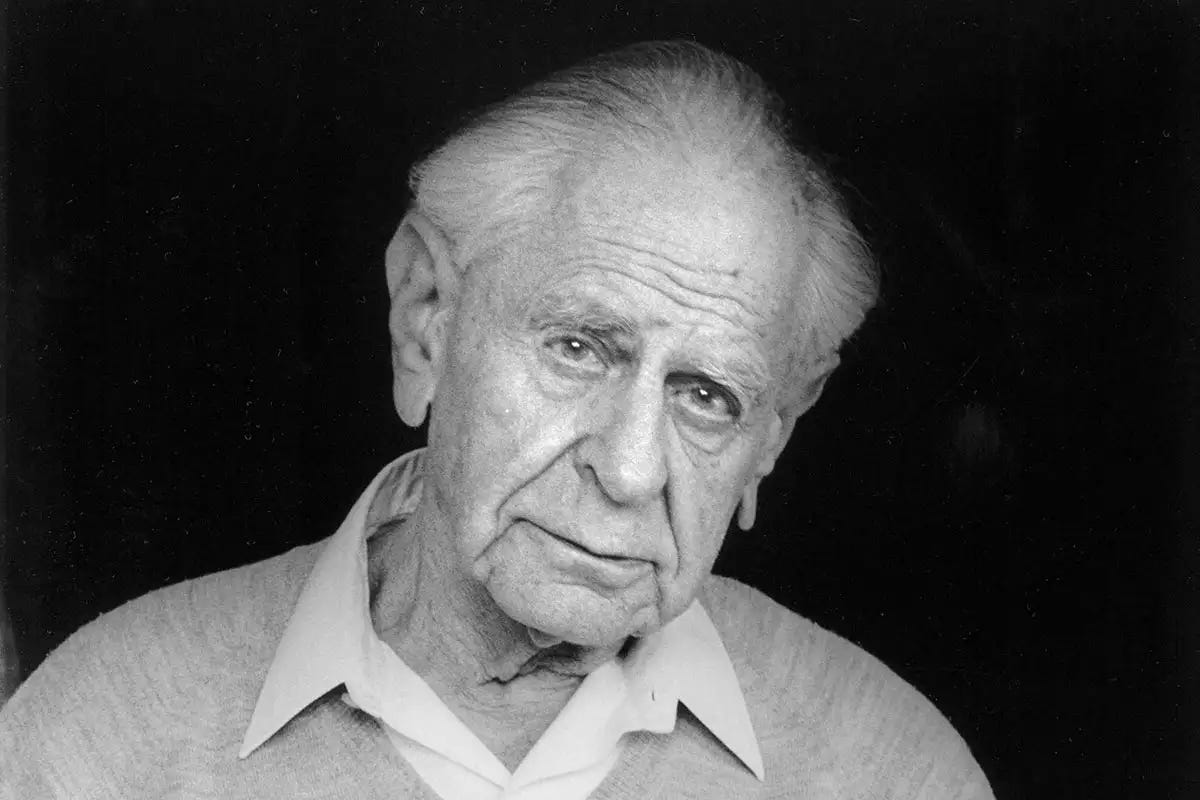

The concept was popularized by philosopher Karl Popper, who argued that real knowledge advances through disproving false ideas. For example, the statement "All crows are black" is falsifiable because finding a single white crow would disprove it. However, the statement "Some supernatural force controls everything" is not falsifiable because there is no way to test or disprove it.

Why Do We Need It?

Falsifiability helps us think clearly, make better decisions, and avoid falling for false beliefs. Here’s why it matters:

Prevents Confirmation Bias: We tend to seek information that supports what we already believe. Falsifiability forces us to look for contradictory evidence, ensuring we don’t fall into an echo chamber.

Example: If you believe “Ayurvedic medicines always work better than allopathic treatments,” you should seek scientific studies that compare their effectiveness rather than relying only on traditional beliefs.

Encourages Critical Thinking: It pushes us to ask, “What evidence would prove me wrong?” leading to stronger, more logical arguments.

Example: A student preparing for a UPSC exam assumes, “I know the syllabus well.” A falsifiable approach would be to take mock tests and evaluate weak areas instead of assuming mastery.

Improves Decision-Making: By testing whether our assumptions hold up against evidence, we can make more informed choices in business, studies, and policies.

Example: An entrepreneur believes their startup idea will succeed in India’s Tier-2 cities. Instead of relying on personal confidence, they should conduct surveys and market research to verify the demand.

Separates Science from Pseudoscience: Genuine knowledge grows when we can test and refine our ideas. Pseudoscience thrives on claims that cannot be disproven.

Example: Astrology suggests that a person’s future is based on their birth chart, but it does not offer a way to scientifically test these predictions. On the other hand, economic forecasting models are tested against real-world data and revised if they fail.

Application in Daily Life

For Students

Studying Smart: If you believe "I always fail in math," try to falsify it. Ask, “Have I ever passed a math test?” Finding one case where you did well breaks the negative belief and allows you to improve.

Choosing the Right Study Techniques: Instead of assuming that a particular method works best, test it. If it fails under certain conditions, you adapt.

For Youth & Entrepreneurs

Validating Business Ideas: Instead of assuming “My product will sell because I like it,” try to disprove it. Conduct market research and gather real feedback. Many startups fail because they don't question their assumptions.

Making Investment Decisions: Before putting money into stocks or mutual funds, ask: “What evidence would show that this is a bad investment?”

For Government Servants & Policymakers

Policy Effectiveness: Instead of assuming a new government scheme will work, ask what data could prove it ineffective. This helps in making evidence-based policies.

Public Administration: If an officer believes, “This new road project will reduce traffic,” they should consider what data might show otherwise and plan accordingly.

Global and Indian Examples

Global: The theory that the Earth is flat is not falsifiable in the scientific sense because its believers often ignore evidence. In contrast, Einstein’s theory of relativity was falsifiable and tested multiple times, strengthening its validity.

India: The “Swachh Bharat Abhiyan” aimed to improve cleanliness. Instead of assuming its success, policymakers tracked sanitation data, public adoption rates, and on-ground changes. By testing its effectiveness, adjustments could be made to improve outcomes.

Final Checklist

Does my belief/assumption have a way to be tested and proven wrong?

Am I actively seeking information that could challenge my viewpoint?

If I were wrong, what evidence would prove it?

Am I open to changing my opinion if strong contrary evidence appears?

Before making a decision, have I considered what could go wrong and tested it?

Conclusion

Falsifiability is not about proving everything wrong—it’s about ensuring that our ideas stand up to scrutiny. Whether you're a student, an entrepreneur, or a policymaker, applying this mental model can lead to smarter choices, stronger arguments, and a clearer path forward. By embracing the possibility of being wrong, we actually get closer to being right.

Best Wishes !